The Mathematical Case for Monkeys Producing Shakespeare—Ultimately

An infinite variety of random occasions can produce absolutely anything if in case you have quintillions of years to attend

Though monkeys have a excessive degree of intelligence, they’re unlikely to supply Shakespeare’s works—until you give them infinite time.

AdrianHillman/Getty Pictures

In one of many most weird analysis experiments within the historical past of arithmetic, researchers on the College of Plymouth in England gave six Celebes crested macaques on the close by Paignton Zoo a keyboard. From Could 1 to June 22, 2002, the animals let off steam by banging on the keys. The letters they typed have been transmitted to the Web. The scientists’ purpose was to check the “infinite monkey theorem”: the concept that a monkey typing randomly on a keyboard will, after an infinite period of time, produce each conceivable textual content—together with the full works of Shakespeare.

However—shock, shock—the primates’ poetry fell brief. After greater than seven weeks, the macaques produced just one five-page doc, consisting virtually completely of the letter “S.” The researchers nonetheless launched the consequence as a e book.

In protection of Elmo, Gum, Heather, Holly, Mistletoe and Rowan—the six macaques who participated on this experiment—they didn’t have an infinite period of time for his or her work. Nonetheless, the consequence was sobering. It appears extremely questionable that these monkeys would have produced Hamlet or the “Scottish play.”

On supporting science journalism

In the event you’re having fun with this text, contemplate supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you’re serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales concerning the discoveries and concepts shaping our world in the present day.

Though the research by no means disproved the infinite monkey theorem, it confirmed that monkeys will not be essentially superb candidates for producing random content material in the best way the concept’s creator had assumed. The infinite monkey theorem owes its title to mathematician Émile Borel, who used the animals metaphorically for example his idea of chance in 1913. The concepts behind the concept are a lot older, nevertheless. In antiquity, Roman thinker and politician Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote that one may “believe that if a great quantity of the one-and-twenty letters, composed either of gold or any other matter, were thrown upon the ground, they would fall into such order as legibly to form [the epic poem] the Annals of Ennius. [But] I doubt whether fortune could make [even] a single verse of them.”

Because the Paignton Zoo macaques illustrate, mathematicians have taken inventive steps to discover this risk. At this time analysis means that Cicero was incorrect: poetry can emerge out of this train in randomness, offered you’ll be able to wait a really very long time.

The Likelihood of a Specific Phrase Showing

Let’s test this concept with a easy instance. How doubtless is it that you’ll get the phrase “banana” fully by likelihood whenever you randomly press a collection of letter keys for a given variety of occasions? (On this situation, you don’t press any numbers or particular characters.) In the event you press six keys consecutively, every chosen at random, the chance is (1⁄52)6 = 1⁄19770609664, which is about 5 billionths of 1 p.c. In different phrases, the chance of not typing banana is 1 – (1⁄52)6, which is sort of a chance of 1. Total, it’s subsequently not possible to get the phrase banana if you happen to press six keys at random. However what if you happen to hit the keys for longer?

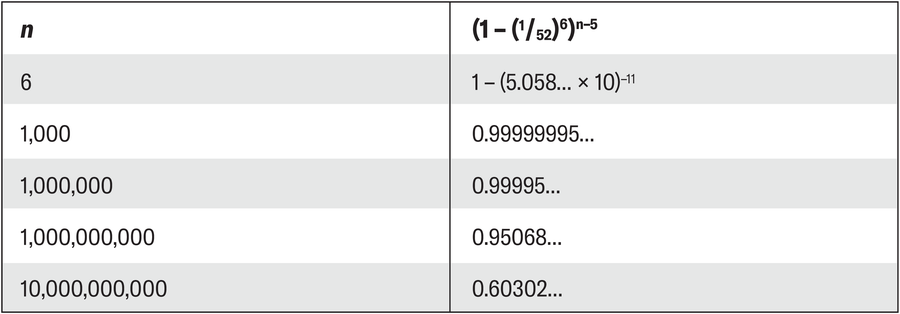

In the event you randomly press a sequence of seven keys, there are two consecutive segments of six letters that may type the specified phrase. With eight keystrokes, there are three strings of six letters, and so forth. In the event you hit the keyboard n occasions at random, the chance that the phrase banana is not going to seem wherever within the string is (1 – (1⁄52)6)n–5. For growing values of n, the chances that “banana” is not going to seem step by step lower:

Manon Bischoff/Spektrum der Wissenschaft, restyled by Amanda Montañez

Thus, the chances that “banana” will seem step by step enhance: In the event you randomly press a key on a keyboard 10 billion occasions, the chance of the phrase showing someplace is abruptly round 40 p.c. The bigger n turns into, the nearer the chance of discovering the phrase banana approaches one. In fact, the consequence additionally applies to different sequences of letters, phrases and even whole sentences and books. Subsequently, from a mathematical perspective, Cicero was incorrect.

The Infinite Monkey Theorem in Apply

In 2024 information analyst Ergon Cugler de Moraes Silva of the College of São Paulo in Brazil needed to seek out out how lengthy it could take, on common, to really get hold of a piece by Shakespeare by likelihood. As a substitute of monkeys, he programmed a personality generator. As described in a preprint paper, his method was designed to quickly spit out a number of hundred pseudorandom areas, punctuation and letters (in each higher and decrease case) every second till a well-known sentence from Hamlet appeared: “To be, or not to be, that is the Question” (together with the areas).

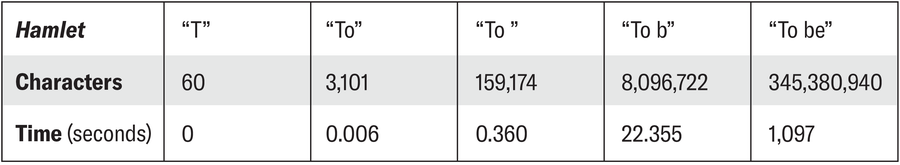

Cugler proceeded in a number of steps. First, he examined how lengthy it takes on common to seek out “T” in isolation. He repeated that process 10 occasions after which recorded the typical time and variety of characters required to generate the specified output. Then he repeated this process to find out how lengthy it could take to randomly generate “To” after which did so once more for “To” adopted by an area, and so forth.

Because the desk beneath reveals, his program needed to randomly generate round 60 characters to supply “T” and generated a mean of 345,380,940 characters for “To be.” These two phrases additionally took his program about 1,100 seconds (a little bit greater than 18 minutes).

Manon Bischoff/Spektrum der Wissenschaft, restyled by Amanda Montañez

At this level Cugler hit a roadblock. Given the rise in time required for accurately producing the subsequent character within the sentence, he realized the duty may doubtlessly require his program to maintain spitting out characters till the tip of humanity (assuming the computer systems concerned would proceed to perform for that lengthy). So in a second step, Cugler designed a program that used the beforehand decided information to extrapolate the variety of characters and computing time required to generate the complete sentence.

Cugler’s calculation confirmed that it could take an excessive quantity of persistence for “To be, or not to be, that is the Question” to seem: about 2.68 x 1069 characters must be generated, which might take about 2.95 x 1066 seconds, or 9.35 x 1058 years.

Since our universe is estimated to be 13.8 billion years previous, we must wait almost 7 x 1048 occasions so long as the time that has handed between the massive bang and in the present day. And all this simply to supply a single sentence from Hamlet by likelihood. On this respect, Cicero was proper: it is rather unlikely that likelihood will produce even a single readable verse of a poem—or another textual content—after a finite period of time.

This text initially appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft and was reproduced with permission.