Indigenous individuals in southern Africa could have been portray long-extinct creatures from 260 million years in the past, even earlier than Western archaeologists described the fossils.

In a thought-provoking new paper, evolutionary biologist Julien Benoit argues that the rock work of La Belle France within the Free State Province of South Africa are an ignored type of Indigenous paleontology.

The depiction of a tusked animal, which was painted almost two centuries in the past, might be not a made-up creature, Benoit explains, however a recreation of a beast that when lived within the area greater than 260 million years in the past.

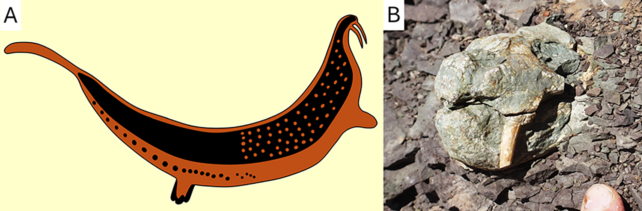

Within the portray, the creature is lengthy and skinny, which is why the rock panel known as the Horned Serpent.

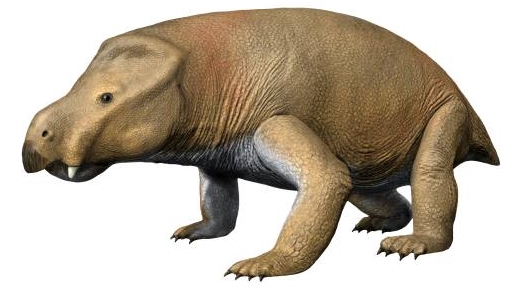

However Benoit, who works on the College of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, has a unique perspective. He says the animal resembles a dicynodont – a four-legged, toothless and tusked ancestor of at the moment’s mammals, whose fossils are considerable and conspicuous within the Karoo Basin.

This basin is described by some as a “palaeontological wonderland“. It covers a lot of what we now know as South Africa, though the fossils deposited right here got here from earlier than the Gondwana supercontinent broke up.

Benoit argues that the rock wall portray of a toothed creature, made by the ǀXam-ka ǃʼē individuals, is suggestive of a ‘geomyth’ – an oral or written custom used to elucidate geological occasions and phenomena, like fossils or pure options of the panorama.

The curve of the creature’s backbone is harking back to the ‘dying pose’ usually seen within the fossil preparations of dicynodonts.

“The painting was made in 1835 at the latest, which means this dicynodont was depicted at least ten years before the western scientific discovery and naming of the first dicynodont by Richard Owen in 1845,” says Benoit.

“This work supports that the first inhabitants of southern Africa… discovered fossils, interpreted them and integrated them in their rock art and belief system.”

In accordance with reporting from The New York Instances, Benoit first observed the resemblance between the Horned Serpent and a dicynodont in a guide from the Thirties. When he went to see the unique art work for himself, he discovered a number of uncovered fossils of dicynodonts within the neighborhood.

The Indigenous cultures of southern Africa are recognized collectively as San, and in keeping with colonist accounts, a neighborhood San fantasy tells of enormous animals, larger than hippos or elephants, that when roamed the world.

Right this moment, archaeological proof means that San ancestors discovered and transported fossils like these over nice distances.

In a 2019 paper, Benoit, paleontologist Charles Helm, and a number of other different colleagues argued that there was a “rich, underappreciated body of evidence for Indigenous awareness of fossils and geological phenomena.”

In time, they predicted a “diverse non-western, Indigenous palaeontological and geomythological heritage will probably become evident in southern Africa.”

The portray of a tusked animal in Karoo is Benoit’s first fleshed-out instance.

Maybe the ǀXam-ka ǃʼē individuals interpreted the skulls of dicynodonts as once-living creatures, integrating the animals into their worldview and their artwork.

The downturned tusks on the Horned Serpent panel are pointed in the identical path as dicynodont tusks – the alternative to elephants and warthogs. The truth is, no dwelling animal in Africa has tusks like this.

“The skin of the tusked animal is dotted,” writes Benoit, “which is not unusual in San rock art, but is also consistent with the warty mummified skin preserved in some dicynodont fossils in the area.”

Benoit’s claims are nearly sure to draw heavy debate over the potential for historic cultures to interpret fossils as intact animals. Claims of protoceratop fossils inspiring myths of griffins, for instance, have lately drawn criticism from researchers who level out a scarcity of supporting proof.

The portray could possibly be interpreted as a seal consuming a fish or a land animal consuming a snake. However the U-shape is simply too brief for that, Benoit argues, and often in San rock artwork, snakes and fish have extra figuring out options. The traces are additionally too thick to be whiskers or blood, he says.

“Even if one considers that the Horned Serpent panel has a purely spiritual meaning, it does not invalidate the hypothesis that the tusked animal itself may have been imagined based on a dicynodont fossil,” argues Benoit.

“The spiritual and paleontological interpretation of this painting are not mutually exclusive.”

The research was printed in PLOS ONE.