An experiment in Sweden has demonstrated management over a novel sort of magnetism, giving scientists a brand new strategy to discover a phenomenon with large potential to enhance electronics – from reminiscence storage to power effectivity.

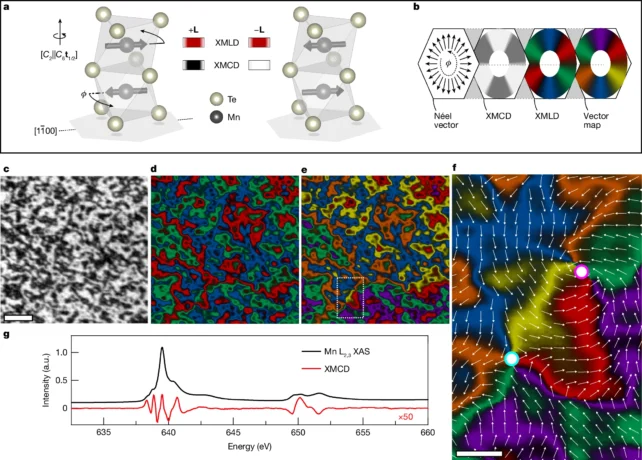

Utilizing a tool that accelerates electrons to blinding speeds, a staff led by researchers from the College of Nottingham showered an ultra-thin wafer of manganese telluride with X-rays of various polarizations, to disclose adjustments on a nanometer scale reflecting magnetic exercise not like something seen earlier than.

For a reasonably mundane chunk of iron to rework into one thing slightly extra magnetic, its constituent particles have to be organized in order that their unpartnered electrons align based on a property referred to as spin.

Just like the spin of a ball, this quantum function of particles has an angular push to it. Not like the rotation of a bodily object, this push solely is available in certainly one of two instructions, conventionally described as up and down.

In non-magnetic supplies, these come as a pair of 1 up and one down, canceling one another out. Not so in supplies like iron, nickel, and cobalt. In these, lonely electrons can be part of forces in a reasonably extraordinary method.

Arranging the remoted spins may end up in an exaggerated north-and-south drive we would use to choose up paper clips or stick youngsters’s drawings to fridge doorways.

By the identical reasoning, encouraging the unpartnered electrons to rearrange themselves in ways in which fully cancel out their spin-based orientations can nonetheless be thought-about a type of magnetism – only a reasonably boring one that appears completely inactive from a distance.

Often known as antiferromagnetism, it is a phenomenon that has been theorized and tinkered with for the higher a part of a century.

Extra not too long ago, a 3rd configuration of particles in ferromagnetic supplies was theorized.

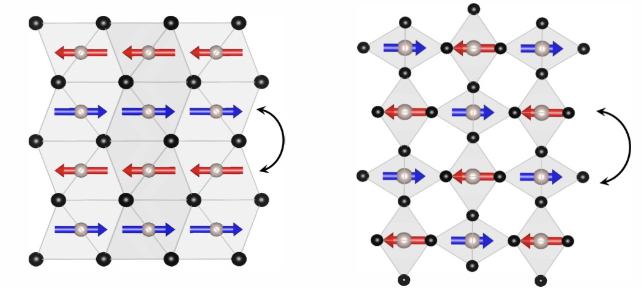

In what’s known as altermagnetism, particles are organized in a canceling vogue like antiferromagnetism, but rotated simply sufficient to permit for confined forces on a nanoscale – not sufficient to pin a grocery listing to your freezer, however with discrete properties that engineers are eager to govern into storing knowledge or channeling power.

“Altermagnets consist of magnetic moments that point antiparallel to their neighbors,” explains College of Nottingham physicist Peter Wadley.

“However, each part of the crystal hosting these tiny moments is rotated with respect to its neighbours. This is like antiferromagnetism with a twist! But this subtle difference has huge ramifications.”

Experiments have since confirmed the existence of this in-between ‘alter’ magnetism. Nevertheless, none had instantly demonstrated it was attainable to govern its tiny magnetic vortices in ways in which would possibly show helpful.

Wadley and his colleagues demonstrated {that a} sheet of manganese telluride only a few nanometers thick could possibly be distorted in ways in which deliberately created distinct magnetic whirlpools on the wafer’s floor.

Utilizing the X-ray-producing synchrotron on the MAX IV Laboratory in Sweden to picture the fabric, they not solely produced a transparent visualization of altermagnetism in motion, however confirmed how it may be manipulated.

“Our experimental work has provided a bridge between theoretical concepts and real-life realization, which hopefully illuminates a path to developing altermagnetic materials for practical applications,” says College of Nottingham physicist Oliver Amin, who led the analysis with PhD scholar Alfred Dal Din.

These sensible functions are all theoretical for now, however have large potential throughout fields of electronics and computing as a sort of spin-based reminiscence system, or serving as a stepping stone in studying how currents would possibly transfer in excessive temperature superconductors.

“To be amongst the first to see the effect and properties of this promising new class of magnetic materials during my PhD has been an immensely rewarding and challenging privilege,” says Dal Din.

This analysis was printed in Nature.