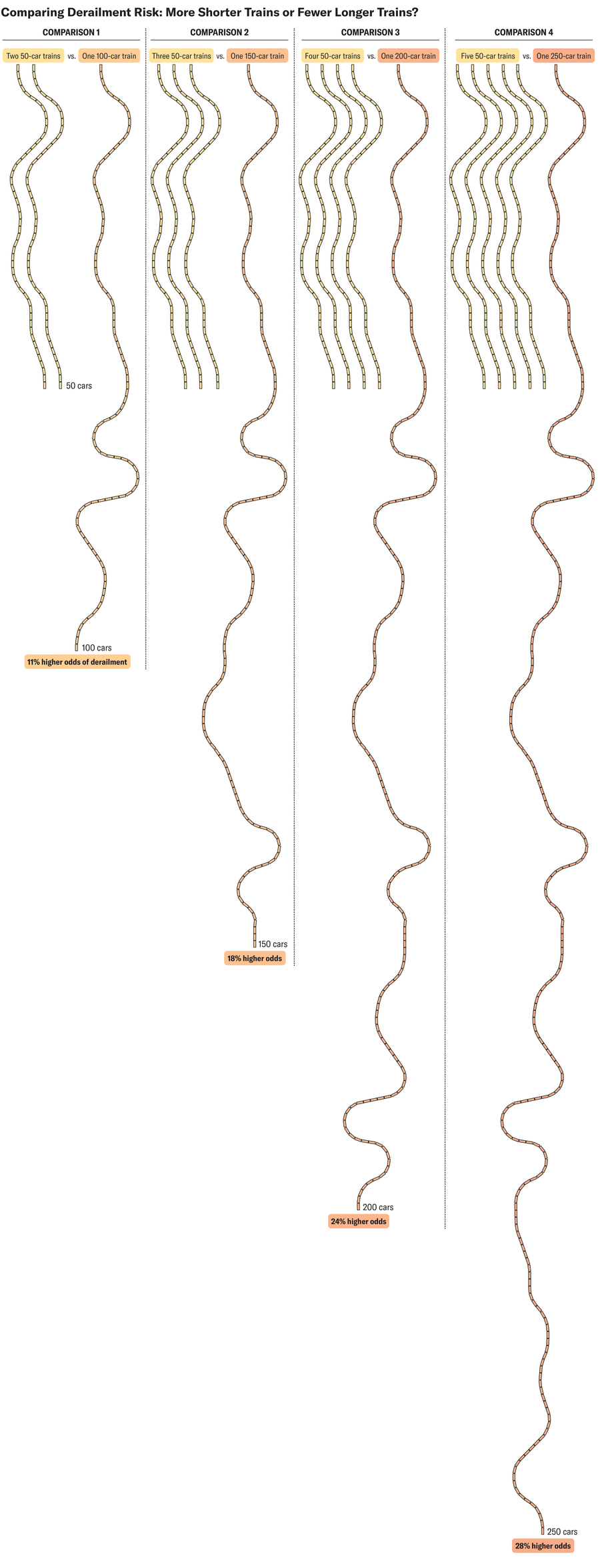

Longer and Longer Freight Trains Drive Up the Odds of Derailment

Changing two 50-car trains with a single 100-car practice will increase the chances of derailment by 11 p.c, in response to a brand new danger evaluation

Steve Proehl/Getty Photos

The U.S. has no federal restrict on freight practice size, leaving the cost-conscious rail business free to experiment with giants like the three.5-mile, nine-locomotive behemoth that chugged from Texas to California in a 2010 check run. However the query of capping size snapped sharply into focus final yr with the fiery crash of a 150-car, 1.75-mile practice carrying chemical cargo by East Palestine, Ohio.

Can a practice be too lengthy? There are nearly no information on any potential risks posed by multiple-mile freight trains. Now, nevertheless, a brand new research printed in Danger Evaluation exhibits that the chances of a practice leaping the tracks will increase because the automobile will get longer. Changing two 50-car trains with one 100-car practice raises the combination odds of derailment by 11 p.c, the research concluded—even accounting for an general lower within the variety of trains operating. A 200-car practice would have a 24 p.c improve in contrast with 4 50-car trains, in response to the research workforce’s calculations.

The elevated danger is relative. “Derailments are uncommon events, fortunately,” says research co-author Peter Madsen, a Brigham Younger College professor of organizational conduct. Throughout the decade-long research interval, he notes, there have been about 300 derailments per yr on mainline U.S. railway tracks. With the freight business’s time and price pressures prone to proceed to mount, security questions might rapidly develop extra pressing.

On supporting science journalism

In the event you’re having fun with this text, think about supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you might be serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales in regards to the discoveries and concepts shaping our world right this moment.

To make their calculations, the research authors wanted to know “the base rate of how many trains of different lengths are traveling on different sections of track,” Madsen says. As a result of these information don’t seem to exist publicly, the workforce used a technique that was beforehand utilized to street automobile crashes. This method, often known as “quasi-induced exposure,” lets researchers consider one kind of crash utilizing one other kind as a baseline. Ideally, comparability occasions aren’t influenced by the variable in query, so “that group of accidents can act as sort of a proxy” for the lacking base charge, he says.

The proxy occasions used for this research had been “beat-the-train” crashes: incidents wherein a driver tried a last-minute sprint by a crossing forward of an oncoming practice. (The authors assumed that drivers didn’t know, or care, in regards to the size of the oncoming practice they did not beat.) Within the absence of higher information, this method gave the authors a window into how lengthy trains are likely to get: A U.S. Division of Transportation company referred to as the Federal Railroad Administration, or FRA, information the lengths of trains concerned in derailments, in addition to these in beat-the-train accidents. Madsen and the workforce in contrast 1,073 of the previous to 1,585 of the latter as a management, matched by county and yr over the 10-year interval.

In accordance with Madsen, that is the primary time quasi-induced publicity has been used to investigate practice dangers. “I hesitate to call it pushing the envelope, but [the study authors] kind of did that,” says Richard Lyles, an emeritus professor of transportation engineering and planning at Michigan State College, who has studied the statistical technique. Provided that quasi-induced publicity can’t produce the true “derailment rate per train-mile traveled,” Lyles says he would place extra emphasis on the research’s normal pattern than on the precise odds.

After the 2023 derailment in Ohio, Congress requested that the Nationwide Academies of Science, Engineering and Drugs (NASEM) type a committee to research trains longer than 7,500 ft (about 1.4 miles). That committee has seen the Danger Evaluation research however, by a NASEM transportation board program officer, declined to touch upon it. The FRA, in the meantime, is reviewing the paper “to fully understand the methodology used and conclusions drawn,” says the company’s public affairs deputy director, Warren Flatau.

Jessica Kahanek, assistant vp of communications on the American Affiliation of Railroads, disputes the research’s danger estimates. “The BYU study fails to take into account the different types of trains or different car types,” she says. “For example, a 50-car train in the study could mean a 2,600-foot coal unit train, 10,000-foot intermodal train or 5,000-foot manifest train.”

Madsen says he and his workforce are “pretty confident” of their calculations, having managed for the variables that they may, corresponding to time of day. “I can understand why [industry groups] don’t like the result. And we’re certainly not trying to argue that longer trains should never be allowed,” he says. Lengthy trains can scale back gasoline consumption and shrink operational prices, because the research authors word. “We just wanted to add a piece of evidence to the discussion.”

Railroad employees corresponding to Jared Cassity, a former locomotive engineer and chief of security for the Worldwide Affiliation of Sheet Steel, Air, Rail and Transportation Staff Transportation Division (SMART-TD) labor union, are fearful about lengthy trains, nevertheless. He likens a practice to a Slinky toy; there’s some slack in a freight practice due to the coupling gadgets, nicknamed knuckles, that hyperlink every automobile. Cassity says he’s notably involved about blended hundreds in lengthy trains—when what would have been a number of smaller trains are mixed right into a single lengthy one—particularly if empty vehicles are positioned in entrance of vehicles stuffed with cargo. If shifting a uniformly loaded practice is like tugging a Slinky throughout a desk, he says, then battling the inertia of an extended, heterogenous practice may be like making an attempt to regulate the identical spring with a two-pound brick connected to its finish.

“We desperately need a law in this country to cap the length of a train,” Cassity says. “We need to know what too long is, and we need to know what the limit is going to be.” The massive image of the Danger Evaluation research is right, in his view: “They’re seeing the reality that long trains derail more often than shorter trains,” Cassity says.