Given half an opportunity, lions aren’t above chewing on the occasional Homo sapien that may stray unguarded into their territory. Thankfully, few of the African massive cats have ever made a behavior of actively searching for out people to dine upon.

There are exceptions, after all. One of the crucial infamous occurred in Kenya’s Tsavo area in 1898, when two male lions spent months terrorizing employees constructing a railroad bridge throughout the Tsavo River.

The century-old enamel of those lions – lengthy mythologized as ‘man-eaters’ – are actually revealing new secrets and techniques, together with not simply whether or not they ate people but in addition clues as to why.

Utilizing latest advances in strategies for sequencing and analyzing outdated and degraded DNA, researchers from the US and Kenya investigated animal hairs caught within the lions’ enamel.

They report their findings in a new research, together with particular animals the lions ate.

Perception like this may assist us not solely fact-check tales in regards to the episode, but in addition higher perceive what may drive wild predators to behave so unusually.

The primary experiences of lion assaults started in March 1898, shortly after the arrival of Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson, a British military officer and engineer overseeing the undertaking to attach the interiors of Kenya and Uganda with a railway.

The British had introduced in hundreds of employees to construct the bridge, largely from India, housing them in camps spanning a number of miles, Patterson wrote.

Patterson initially doubted experiences of two employees kidnapped by lions, however was satisfied weeks later when Ungan Singh, an Indian navy officer accompanying him, suffered the identical destiny.

Patterson spent that evening in a tree, promising to shoot the lion if it returned. He did hear “ominous roaring,” he wrote, then an extended silence, adopted by “a great uproar and frenzied cries coming from another camp about half a mile away.”

The following morning, he discovered a lion had attacked one other a part of the camp.

Thus started a prolonged marketing campaign by Patterson and others to kill the culprits: two massive, maneless male lions. Maneless males are extra widespread in some areas, together with Tsavo, presumably as a result of native local weather or vegetation.

The assaults as soon as abruptly stopped for just a few months, Patterson notes, though “from time to time we heard of their depredations in other quarters.”

When the lions lastly returned, they appeared even bolder: As an alternative of attacking individually as earlier than, they usually entered camps collectively.

Patterson ended up killing each lions that December.

The lions’ ultimate dying toll stays unclear; some estimates vary as excessive as 135, although a 2001 research finds the numbers had been more likely to be nearer to round 30 – a determine that, though far smaller, is in no way insignificant.

Patterson saved the lions’ stays, finally promoting them to the Area Museum of Pure Historical past in Chicago in 1925.

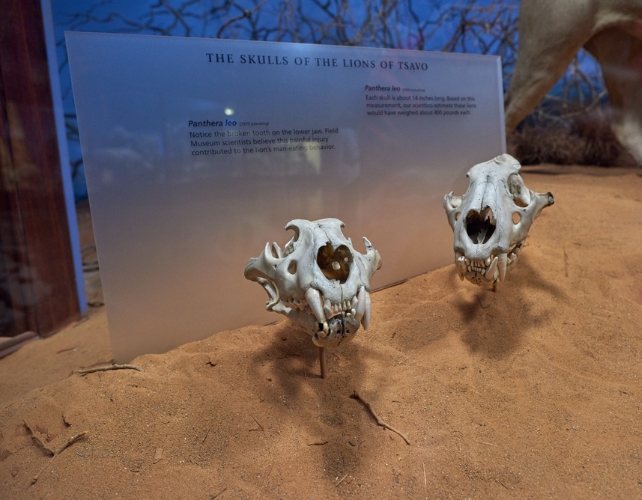

A long time later, when ecologist Thomas Gnoske, the museum’s collections supervisor, discovered the lions’ skulls in storage, he seen hair fragments caught in uncovered tooth cavities.

Some scientists speculate the lions hunted people exactly due to broken enamel, which may have made it laborious to subdue bigger prey.

In any case, the harm appears to have preserved clues in regards to the lions’ food regimen. Gnoske and colleagues have now performed an in-depth research of the hairs, together with microscopic and genomic analyses.

First, they needed to affirm the hairs’ age, explains co-author Alida de Flamingh, a conservation biologist on the College of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“We look to see whether the DNA has these patterns that are typically found in ancient DNA,” de Flamingh says.

As soon as the samples had been verified, the authors homed in on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). It is extra plentiful in cells than nuclear DNA, and hair may protect mtDNA and restrict contamination, which helps with older samples.

”And because the mitochondrial genome is much smaller than the nuclear genome, it’s easier to reconstruct in potential prey species,” de Flamingh provides.

The hairs weren’t in nice situation, however they nonetheless yielded usable mtDNA. Some hairs got here from the lions themselves.

The remaining originated largely from an unsurprising mixture of native ungulates – with one notable exception. The enamel of those notorious man-eaters did, in reality, comprise human hair.

“Analysis of hair DNA identified giraffe, human, oryx, waterbuck, wildebeest and zebra as prey, and also identified hairs that originated from lions,” de Flamingh, Gnoske, and workforce write.

The lions’ mtDNA suggests they had been brothers, as suspected. They’d eaten a minimum of two giraffes, based on the evaluation, and a neighborhood zebra.

The workforce additionally created a database of mtDNA profiles for potential prey species occupying the lions’ habitat in 1898.

Discovering wildebeest mtDNA was odd, they observe, for the reason that nearest wildebeests again then lived some 50 miles away. However when Patterson reported an prolonged lull in assaults, perhaps the lions had been off looking wildebeests.

It was additionally noteworthy to seek out only one buffalo hair, the authors add, and no buffalo mtDNA. “We know from what lions in Tsavo eat today that buffalo is the preferred prey,” de Flamingh says.

That would trace at why these lions hunted individuals.

“Patterson kept a handwritten field journal during his time at Tsavo,” says paleoanthropologist Julian Kerbis Peterhans of Roosevelt College and the Area Museum. “But he never recorded seeing buffalo or indigenous cattle in his journal.”

Rinderpest, a viral illness of ungulates, had been launched from India to Africa years earlier. It obliterated buffalo and cattle throughout the area within the Eighteen Nineties, presumably forcing some lions to seek out new prey.

For this research, the researchers opted to not conduct additional evaluation of the human hairs to establish potential victims.

“There may be descendants still in the region today, and to practice responsible and ethical science, we are using community-based methods to extend the human aspects of the larger project,” they write.

The research was printed in Present Biology.