As a graphics editor at Scientific American, I spend plenty of time fascinated about and visualizing knowledge—together with knowledge on medical dangers. So after I received pregnant in 2018, I used to be ready for issues to be sophisticated. A number of the most typical points loomed in my thoughts: for instance, as many as one in 5 recognized pregnancies ends in miscarriage, and an estimated 13 p.c of expectant individuals develop probably harmful blood stress problems. When no such issues arose in my being pregnant, I exhaled and concluded that I used to be fortunate. I didn’t contemplate the types of diagnoses or occasions that affected lower than, say, 1 p.c of pregnancies. These circumstances, I reasoned, had been uncommon.

How individuals take into consideration uncommon occasions—particularly unwelcome ones comparable to traumatic medical episodes or distressing diagnoses—appears to fluctuate significantly relying on whether or not they have been instantly affected by one. From my perspective one necessary implication of this phenomenon is that individuals mentally reframe the time period “rare” because it applies in their very own life. When an individual is informed {that a} specific dangerous consequence is extraordinarily unlikely after which it occurs anyway, they will understandably lose their belief in statistics as a dependable information for decision-making, the implications of which will be dangerous.

At round eight months of being pregnant, I complained to my midwife of some itchy pores and skin rashes that had popped up just lately. She assured me that it was in all probability nothing to fret about however really helpful a blood check to examine for cholestasis. I had come throughout the time period in my “pregnant and itchy” Google searches, so I knew that intrahepatic cholestasis of being pregnant (ICP) was a liver situation that may develop within the third trimester and that it got here with main dangers for the fetus, together with stillbirth. And I understood that the remedy was mainly to get the infant out as quickly as potential. However my signs didn’t fairly line up with the most typical shows of ICP. Plus, the Web informed me, the situation impacts solely about one in 1,000 pregnant individuals within the U.S. It didn’t really feel remotely probably that I’d be that one.

On supporting science journalism

For those who’re having fun with this text, contemplate supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you might be serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales in regards to the discoveries and concepts shaping our world at present.

A number of days later I received an pressing telephone name. You see the place that is going: my cholestasis check had come again constructive, and my midwife was advising me to go to the hospital that night to be induced. Once more my data-oriented mind kicked in. What, precisely, was the stillbirth danger if I had been to hold to time period? About 3 p.c, she informed me. Effectively, after apparently defying one-in-a-thousand odds, three-in-a-hundred sounded alarmingly possible. My fingers shook as I known as my husband. “It looks like we’re going to have a baby sooner than we thought,” I informed him.

In some ways, an individual’s perception that the unlikely can occur to them is probably helpful. Take, for instance, the danger of dying from pores and skin most cancers (a destiny affecting 0.002 p.c of the U.S. inhabitants). An individual who takes that danger critically would possibly elect to put on sunscreen every day—a wholesome alternative with just about no draw back. As for my very own determination to have labor induced to attenuate dangers to my baby, the result included an emergency cesarean part, a process that comes with main dangers and which can have been pointless had I waited for labor to start spontaneously. (Fortunately, the surgical procedure went easily, and I used to be left with a wholesome child and no regrets.)

In sure circumstances, although, overestimating the danger of unlikely penalties can complicate what needs to be comparatively simple health-related selections. Think about somebody weighing whether or not to obtain a routine vaccination that comes with a danger of uncomfortable side effects which can be severe however vanishingly uncommon. If this particular person has been as soon as bitten by a purportedly one-in-a-million form of occasion, they is likely to be twice shy when confronted with one other danger whose chances are characterised in the same method. However, by refusing vaccination, they danger the much more believable consequence of catching a preventable an infection and spreading it to susceptible members of their neighborhood.

To fight the destructive results of this model of danger aversion, it appears necessary to extend consciousness of some key ideas. First, there’s a essential distinction between the likelihood of experiencing any uncommon medical prognosis and that of struggling a particular one. The Nationwide Group for Uncommon Issues (NORD) defines a uncommon illness as one affecting fewer than 200,000 individuals within the U.S., which works out to lower than 1 p.c of the inhabitants. However all 10,000 or so uncommon illnesses collectively have an effect on greater than 30 million individuals within the U.S. That’s about one in 10 People. Uncommon illnesses as a bunch, it seems, should not uncommon in any respect.

Extending this precept to extra self-contained medical occasions comparable to uncommon uncomfortable side effects, it’s tougher to quote particular knowledge as a result of the class is so broad. However given how lengthy the typical particular person lives and the way steadily they make well being selections that carry some danger, not solely is it unsurprising that somebody would possibly expertise one thing uncommon—it might be extra exceptional in the event that they by no means did.

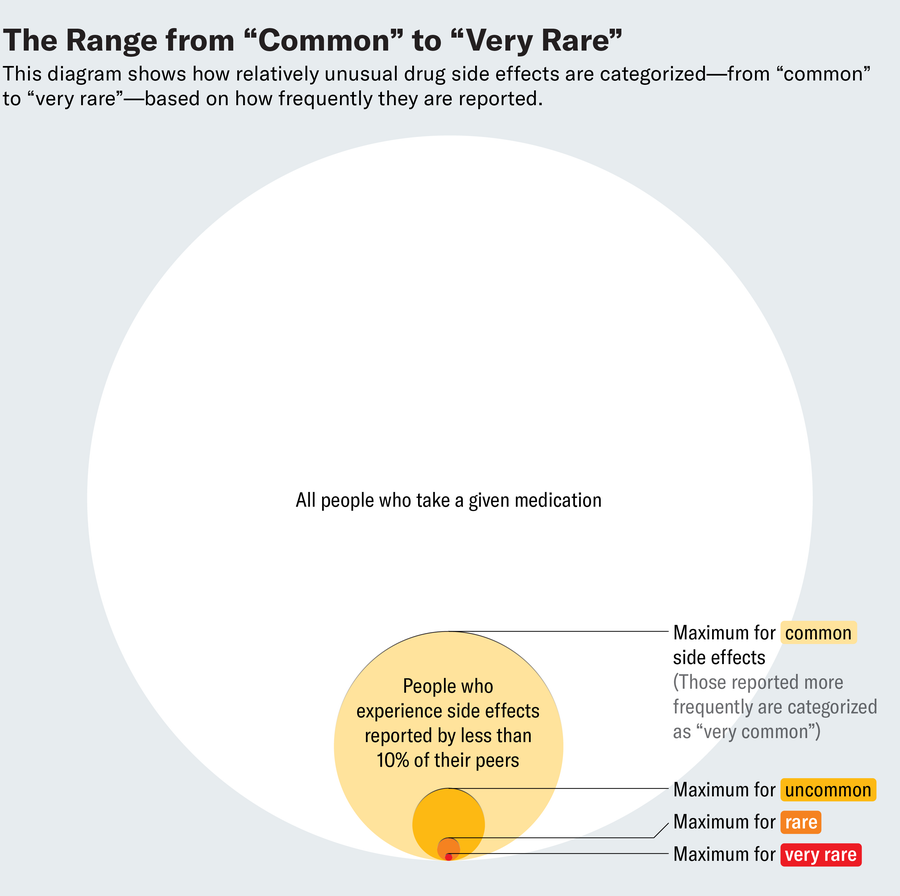

Second, terminology is important. Colloquially, the expressions “uncommon,” “rare” and “very rare” don’t really feel that totally different. However technically, they will differ by a number of orders of magnitude. Within the context of drug uncomfortable side effects, these phrases cowl a variety of statistical odds from as much as one in 100 individuals to fewer than one in 10,000.

Including to the complexity of danger evaluation, medical dangers can fluctuate broadly amongst totally different populations. Total, girls have a 13 p.c likelihood of creating breast most cancers of their lifetime. However for these with sure mutations within the genes often called BRCA1 or BRCA2, the danger exceeds 60 p.c. Because of this, members of the latter group would possibly contemplate a prophylactic mastectomy, whereas for others, the advantages of surgical procedure are unlikely to outweigh the drawbacks. In fact, there are lots of extra circumstances the place particular person danger degree is tougher to calculate. However it will probably nonetheless be worthwhile to interact with what is thought and attempt to estimate the place one would possibly fall inside a variety. (To wit, I may need been extra ready for my constructive ICP check had I learn slightly additional: prevalence amongst Latina girls is estimated at about 6 p.c).

Statistics apart, individuals are notoriously irrational in how they consider dangers. We’re extra averse to the destructive results of our personal selections in the event that they outcome from motion quite than inaction. (That’s why the prospect of getting a flu shot and struggling debilitating uncomfortable side effects can overshadow that of catching the flu after skipping the vaccine, regardless that the latter is much extra more likely to happen.) And we are sometimes extra simply swayed by feelings—rooted both in our personal experiences or in poignant tales from others in our lives—quite than numbers. So finally, the treatment for this drawback goes past pedantic classes in medical danger knowledge. It requires us to interact critically with our personal human biases and, when vital, push previous them to make smart selections for ourselves and our communities.

That is an opinion and evaluation article, and the views expressed by the creator or authors should not essentially these of Scientific American.